Zoning in permaculture design is a concept that you will soon encounter if you look into permaculture. But this can be confusing to those who are not familiar within this concept and what it entails. Site analysis – observation and careful consideration is crucial in permaculture design. In addition to thinking about sectors acting on the site, permaculture zoning is also key.

The design process for a permaculture garden always begins with observation. Designers will look at sectors – sunlight, wind and water. They will look at the topography, and the soil and think about which solutions (which adhere to the ethics and principles above) will work best in a given situation. They will plot existing resources, and think about broader patterns before honing in on more intricate details. All too often, however, designers may overlook the fact that human beings are an important part of the garden system.

We are required to maintain, tend and use land and natural resources to full advantage. The design of a site, therefore, should not only take into account the natural conditions, and the basic elements required for plant life, but also how well it works for people. In undertaking site analysis, patterns of human movement are key within the site itself. In an analysis, and as we begin to form ideas about the layout for various elements within the design, permaculture zoning comes into play.

What is Permaculture Zoning?

The permaculture design process also involves thinking about how humans interact with the garden system as a whole. Zoning, in permaculture, is a way to maximise productivity, reduce waste, and make sure efficiency is maintained. Simply put, it involves placing elements visited most frequently closest to the home, and those you’ll need to visit and manage less further away. The inputs, outputs and characteristics of each element will be considered, so that they can be placed sensibly and practically in relation to one another and the site as a whole. Zoning is all about practicality and time management. It begins with the simple premise that the elements on a site that we visit most often should be closest to the centre of operations.

The Zones in Permaculture Design

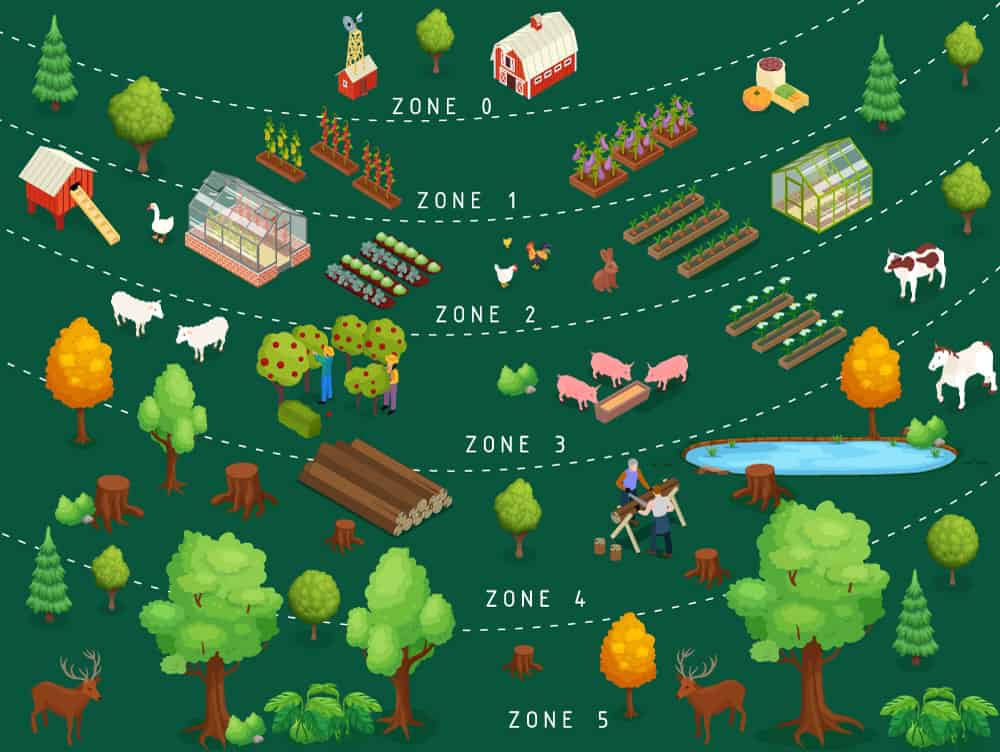

Permaculture designers usually define up to five zones on any site (not including zone zero – the home or centre of operations), though smaller sites will usually only include a couple of these zones. Zones spread out sequentially, larger numbers used to designate areas visited less and less frequently, though the zones may not be placed strictly in order moving out from the centre. Some areas closer to your home but less accessible, for example, may belong to a higher zone.

Zone Zero

Zone zero is the home, or centre of operations. This is the hub, or nexus for the patterns of movement on the site – the journey start point and location of return. Zone zero if often overlooked when it comes to talking about zoning, and permaculture design in general. While we are more used to seeing permaculture design methodology used in relation to land and food production areas, these theories and techniques can also inform home design and use. By bringing permaculture ethics and principles, design and practices in from the garden, right into the hearts of our homes, we can ensure that we have the firm footing required to live as we wish to live.

Zone One

Zone one elements are usually visited most days, if not every day, often multiple times over the course of a day. Annual kitchen gardens, primary outdoors living areas, rainwater harvesting systems, composting systems and perhaps frequently used utility areas like sheds would usually be part of this zone. In zone one, it is especially important to consider how this space interacts with the home, or centre of operations. In most designs, this zone will be most crucial in design, since this is where humans on the site will spend the majority of their time.

Zone Two

Zone two elements still require time and attention, but are visited somewhat less frequently. This zone may include orchards and forest gardens, perennial vegetable beds, garden ponds, perhaps chickens or bees, for example. The elements in these zones can be particularly important in low-maintenance schemes. Since these are the areas that can often take less work than zone one, while still being hugely productive.

Zone Three

Zone three is the zone for farmland arable crops and for bigger livestock on larger sites. Of course, this is zone that will not be present in all designs – especially domestic sites.

Zone Four

Zone four is areas for natural forage and minimal intervention – a woodland area used for fuel or non-timber forest products, for example. This might be a zone where activities like coppicing are undertaken. Or can be a zone of little work, where yields without much if any work are derived.

Zone Five

Zone five is essentially wild – a zone for wildlife, mostly if not entirely untouched and unmanaged by human hand. Zoning is a start point, not an end point for decision making about the positioning of the different elements within a design. But by starting with site and sectors analysis, and zoning, we can form firm foundations. We can form a clear picture of the patterns from which we can move on to the next stages of in-depth decision making and design.

Why We Zone in Permaculture Design

Zoning is all about making the most of time – our own time, and time within the system. Remember, our goal through zoning and the placement of different elements within different zones is to minimise the time it takes us to maintain the systems we create, and make our way throughout the space. Remember, zoning is about how humans interact within a system, rather than directly about the system independent of us. But in holistic design, we must consider our needs and time management alongside other considerations. One of the key things in a permaculture system is joined-up thinking.

All the elements are considered holistically, not just in isolation. A broad view is taken, and all the interconnections are taken into account. In design, we may often overlook the importance of our own role within the system. But there is a common saying that the farmer or gardener’s footsteps are the best fertilizer for a growing system. In other words, the more time we are able to spend in our growing spaces, the more healthy, abundant and productive they can be. Effective zoning can help us ensure that we are able to give our systems the attention they require to optimize results and obtain a yield on our properties.

Positioning Elements Within Different Zones

Considering which zone a certain element should be positioned within is one of the key decisions to make. But it is important to remember that we need to consider layout, access and placement not only with reference to the whole of the site, but also with reference to how we interact with different elements, and how different elements interact with one another.

Remember, we can follow general guidelines relating to which zone different elements are generally placed within. But we should not allow zoning to override other considerations. In some cases, for example, sunlight might restrict how close to a home your primary annual growing areas might be placed. So common sense is required, and placing elements within zones according to the time to be spend there should be viewed as something to aim for in addition to other considerations.

Infrastructure, Systems and Pathways

As well as thinking about zoning on a particular site, permaculture design involves looking at the links between the different zones and elements. In zoning and layout, thinking about key infrastructure elements, systems and pathways is of course vitally important.

Convenient pathways between different elements, as well as how frequently these will be used, should be considered. Pathways which allow for free and easy movement through the space can often be beneficial. It is often important to think about reducing gradient, avoiding uneven surfaces, and keeping pathways wide and clear, especially when accessibility is important for the gardener, farmer, or other users of the space. The specific surface required will of course depend on who will use the space and other factors, but is another important thing to think about in design. You might also wish to think about how specifically access routes will be used. Will people or vehicles use them? Will wheelbarrow access be required? These types of considerations go hand-in-hand with zoning in permaculture design.

Aside from literal access routes like tracks or walking pathways, this also involves thinking about water systems, and systems to maintain fertility on the site, for example. You might think about how earthworks might be used to manage water on the site. Rainwater harvesting and the direction of that water should be considered. And thought should be given to how water with be retailed and used within the landscape. Composting and the routes for organic matter within the system can also be crucial in the determination of layout and placement of features within permaculture design.

Systems Analysis

Moving beyond the idea of zoning, you can make a design allows for ease and convenience and efficient use of time by undertaking a process of systems analysis when deciding where to place it and other elements, on your site. Systems analysis involves looking at all the elements in a system, the inputs, outputs and characteristics of each, before thinking about how they should all best be positioned to minimise the time and effort required to keep the whole system functioning.

Spending a little time thinking about these things before you place your growing areas could help you to save a lot of time later on. Let’s undertake the process of systems analysis for a typical, food-growing annual bed, and see what that might tell us about the best position for this garden element:

Inputs: sunlight; water; human effort; compost; manure; organic matter (mulches); insects and other wildlife (pollinators); seeds & plants.

Outputs: edible harvest; animal feed?; biomass; material for composting.

Characteristics: rich in nutrients, sheltered, etc…

Thinking about the inputs, outputs and characteristics of each element in your organic garden system will also help you determine which elements to include, and the best layout for your space. We can identify the garden elements that will provide the inputs, and those that will accept the outputs, and how the characteristics of each will help us achieve our goals.

The characteristics of an element may also give us ideas as to which other garden elements could benefit from proximity to, or use of, the structure. We can identify the garden elements that will provide the inputs, and those that will accept the outputs. It can be helpful to consider how often you will be taking pathways between the various elements.

For example, you may only move between sources of organic matter and your primary annual growing area a few times a year, but may well need to move between your water source/ rainwater harvesting system and your growing area every day in the summer months. In order to save time and effort, you should position elements between which you must travel frequently as close together as possible.

Remember, zoning can be useful in permaculture to help us make the most of time and space. But in order to fully realise a design that works well in every way, we need to move beyond zoning to really consider the implications of the placement of different elements, and undertake a full and clear analysis of the systems within a site.